The following Articles for the restoration of peace have been agreed upon by the British

Government and the Afghan Government:

ARTICLE 1.

From the date of the signing of this Treaty there shall be peace between the British

Government, on the one part, and the Government of Afghanistan on the other.

ARTICLE 2.

In view of the circumstances which have brought about the present war between the

British Government and the Government of Afghanistan, the British Government, to

mark their displeasure, withdraw the privilege enjoyed by former Amirs of importing

arms, ammunition or warlike munitions through India to Afghanistan.

ARTICLE 3.

The arrears of the late Amir's subsidy are furthermore confiscated, and no subsidy is

granted to the present Amir.

ARTICLE 4.

At the same time, the British Government are desirous of the re-establishment of the

old friendship that has so long existed between Afghanistan and Great Britain, provided

they have guarantees that the Afghan Government are, on their part, sincerely anxious to

regain the friendship of the British Government. The British Government are prepared,

therefore, provided the Afghan Government prove this by their acts and conduct, to

receive another Afghan mission after six months for the discussion and settlement of

matters of common interest to the two Governments and the re-establishment of the old

friendship on a satisfactory basis.

ARTICLE 5.

The Afghan Government accept the Indo-Afghan frontier accepted by the late Amir.

They further agree to the early demarcation by a British Commission of the

undemarcated portion of the line west of the Khyber, where the recent Afghan aggression

took place, and to accept such boundary as the British Commission may lay down. TheBritish troops on this side will remain in their present positions until such demarcation

has been effected.

ALI AHMAD KHAN,A. H. GRANT

Commissary for Home Affairs and Chief of Foreign Secretary to the Government of the Peace Delegation of the AfghanIndia and Chief of the Peace Delegation of Government.the British Government.

ANNEXURE

No. 7-P.O., dated Rawalpindi, the 8th August 1919.

From-The Chief British Representative, Indo-Afghan Peace Conference,

To-The Chief Afghan Representative.

After compliments-You asked me for some further assurance that the Peace Treaty which

the British Government now offer, contains nothing that interfered with the complete

liberty of Afghanistan in internal or external matters.

My friend, if you will read the Treaty carefully you will see that there is no such

interference with the liberty of Afghanistan. You have told me that the Afghan

Government are unwilling to renew the arrangement whereby the late Amir agreed to

follow unreservedly the advice of the British Government in regard to his external

relations. I have not, therefore, pressed this matter: and no mention of it is made in the

Treaty. Therefore, the said Treaty and this letter leave Afghanistan officially free and

independent in its internal and external affairs.

Moreover, this war has cancelled all previous Treaties.-Usual conclusion.

From: C. U. Aitchison, ed. A Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sanads: Relating

to India and Neighbouring Countries. Vol. XIII. Calcutta: Government of India Central

Publication Branch, 1933, 286-288.

This article examines Afghanistan's geopolitical relationship with the British Empire during the 19th and early 20th centuries, focusing on why Afghanistan, despite military interventions and British influence, was never colonized. The article briefly analyzes the Anglo-Afghan wars, the strategic importance of Afghanistan in the Great Game, and the recognition of Afghan sovereignty in 1919.

Strategic Importance of Afghanistan in British Imperial Policy

The Great Game: Examines the strategic competition between the British and Russian Empires and the geopolitical significance of Central Asia.

First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842):

Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880):

Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919):

Britain did not generally intend to colonize Afghanistan; its primary goal was to establish Afghanistan as a buffer state. This aim was part of Britain’s strategy to protect its colonies in India and prevent Russian expansion southward.

Strategic Objective:

Geographical and Cultural Challenges:

Previous Experiences:

Focus on Regional Stability:

Thus, rather than pursuing full colonization, Britain focused on establishing diplomatic relations and strategic agreements to mitigate Russian influence and maintain its desired geopolitical status.

Based on the above, Afghanistan was never a British colony, but throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, like Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey, Afghanistan was significantly influenced by British interests, especially during the Great Game, a strategic rivalry between the British Empire and the Russian Empire over control of Central Asia.

Britain did not intend to colonize Afghanistan; instead, it aimed for Afghanistan to remain an independent country that could function as a buffer state. Britain sought to control Afghanistan through military invasions, leading to the First, Second, and Third Anglo-Afghan Wars. While Britain was able to exert significant influence over Afghanistan’s foreign affairs, particularly after the Treaty of Gandamak in 1879, Afghanistan maintained its internal sovereignty and was never fully colonized.

In 1919, following the Third Anglo-Afghan War, Afghanistan achieved full autonomy from British influence, and this conflict resulted in the Treaty of Rawalpindi, which, although recognizing Afghan independence, essentially acknowledged Afghanistan's autonomy in its foreign affairs.

:Primary Sources

The Treaty of Gandamak (1879): Available in British and Afghan archives.

The Treaty of Rawalpindi (1919): Available in British and Afghan archives.

British diplomatic correspondence and government documents from the India Office Records (IOR), held at the British Library.

Afghan government records, letters, and decrees from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

:Books

Adamec, Ludwig W. Afghanistan, 1900-1923: A Diplomatic History. University of California Press, 1967.

Hopkins, B. D. The Making of Modern Afghanistan. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Ingram, Edward. The Beginning of the Great Game in Asia, 1828–1834. Clarendon Press, 1979.

Ewans, Martin. Afghanistan: A Short History of Its People and Politics. HarperCollins, 2002.

Noelle-Karimi, Christine. The Pearl in Its Midst: Herat and the Mapping of Khurasan (15th-19th centuries). Austrian Academy of Sciences, 2014.

:Journal Articles

Ewans, Martin. "The Second Afghan War and the Garrisoning of Kandahar, 1878-80." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, vol. 28, no. 2, 2000, pp. 50-69.

Kakar, M. Hasan. "The Fall of the Afghan Monarchy in 1929: The Interregnum." International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, 1978, pp. 195-214.

Yapp, M. E. "British Policy in Afghanistan, 1868-1893." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, vol. 31, no. 2, 1968, pp. 285-314.

Tanner, Stephen. "Afghanistan: A Military History from Alexander the Great to the Fall of the Taliban." Journal of Military History, vol. 67, no. 1, 2003, pp. 217-220.

:Theses/Dissertations

Gregorian, Vartan. The Emergence of Modern Afghanistan: Politics of Reform and Modernization, 1880-1946. PhD Dissertation, Stanford University, 1968.

Hanifi, Shah Mahmoud. Connecting Histories in Afghanistan: Market Relations and State Formation on a Colonial Frontier. PhD Dissertation, Duke University, 2002.

:Online Resources

British Library Archives: Access to the India Office Records.

National Archives of Afghanistan: For Afghan governmental documents.

JSTOR: Access to journal articles and book reviews.

Google Books: For accessing older texts and references.

Historical Context and Background:

Dalrymple, William. Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013.

Dupree, Louis. Afghanistan. Oxford University Press, 1980.

Lower Paleolithic

The discovery of Lower Paleolithic tools, dating over 100,000 years ago, east of the brackish lake Dasht-i-Nawur, west of Ghazni, marked a significant finding (L. Dupree, 1974). These tools, mostly made from quartzite, include large flake cores, cleavers, side scrapers, choppers, adzes, hand axes, and proto-hand axes—making them the earliest Lower Paleolithic tools identified in Afghanistan.

In 1966, a team of American archaeologists began excavations at the Darra-i-Kur rock shelter, near Baba Darwesh in Badakhshan, seeking evidence of the migration of Neanderthal-like populations across Eurasia. There, they unearthed hundreds of classic Middle Paleolithic stone tools, dating to around 50,000 years ago. This represented the first scientifically documented Middle Paleolithic tools in Afghanistan (L. Dupree, director).

The team continued their search in 1969, moving west to Gurziwan near Maimana, where additional Middle Paleolithic tools were found, including types that resemble those discovered at Darra-i-Kur. These findings may suggest even older tool types than those from Darra-i-Kur. The tools found north of Dasht-i-Nawur in 1974 included Levallois flakes, scrapers, points, and possible burins, offering further insight into early human toolmaking.

Middle Paleolithic and Neanderthal Man

The tools found at Darra-i-Kur are typically associated with Neanderthal Man, with skeletons discovered in similar contexts, such as at Teshik Tash in Uzbekistan. However, at Darra-i-Kur, a prominent temporal bone was identified with features both modern and Neanderthaloid, suggesting that the area may have been a pivotal site in the evolution of early humans. This could mean that modern Homo sapiens, or at least a variety of early humans, might have developed in northern Afghanistan, potentially reshaping our understanding of human evolution.

Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic period, dating from around 34,000 to 12,000 years ago, saw the development of more sophisticated stone tools. One of the earliest excavated Upper Paleolithic sites in Afghanistan was Kara Kamar, a rock shelter 23 km (14 miles) north of Samangan, which produced tools dating back to approximately 30,000 B.C. (C. Coon, 1954).

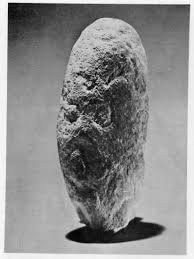

In the Balkh region, further excavations by American archaeologists in the 1960s and 1970s uncovered over 20,000 tools from rock shelters beside the Balkh River, dating to between 20,000 and 15,000 years ago. These tools, renowned for their craftsmanship, led one archaeologist to call the toolmakers "the Michelangelos of the Upper Paleolithic." Among these finds was a small limestone pebble carved with the face of a human, a rare early representation of human figures.

Mesolithic and Neolithic

In the Mesolithic period, approximately 10,000 years ago, Russian archaeologists discovered high-quality microlithic tools in the sand dunes south of the Amu Darya. These tools marked the transition to more complex forms of technology, with geometric shapes and new materials becoming prevalent.

By the Neolithic period, around 9,000 years ago, revolutionary advancements in agriculture and animal domestication occurred. The Neolithic site of Aq Kupruk, in northern Afghanistan, stands out as one of the early centers of plant and animal domestication, linking Afghanistan with the broader Neolithic developments of the Middle East and Central Asia. The evidence at Aq Kupruk supports the theory that the innovations of agriculture spread across the region from this area, extending through Anatolia and Greece.

Further evidence of Neolithic life can be found at Darra-i-Kur, where remains of domesticated goats were discovered, suggesting ritualistic practices and an early understanding of life and death. These burial sites point to the growing complexity of social and religious beliefs during this period.

Bronze Age

As humans advanced in agriculture, they began to establish permanent settlements. Around 5,000 B.C., early peasant farming villages emerged in Afghanistan, such as Deh Morasi Ghundai, southwest of Kandahar. This site, along with others in the region, provided essential insights into early Bronze Age life, where multi-roomed mud-brick structures were found, along with pottery, copper tools, and stone seals. Excavations in the Seistan region and at sites like Said Qala and Shamshir Ghar further reveal the Bronze Age cultural connections between Afghanistan, the Iranian Plateau, and Central Asia.

One notable find was the Khosh Tapa Hoard, uncovered in northern Afghanistan in 1966. This treasure, containing gold and silver goblets decorated with geometric designs and animal motifs, hints at long-distance trade, possibly linking Afghanistan with the ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley.

Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age

The Bronze Age continued to flourish in northern Afghanistan, with the discovery of fine ceramic vessels, weapons, and jewelry at sites like Dashli and the Bronze Age mounds near Daulatabad. These finds offer a glimpse into the daily life and technological prowess of ancient Afghan civilisations.

As the cities of the Indus Valley, such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, grew, they developed complex economic systems that relied on trade and specialization. Evidence from Afghanistan indicates that trade networks stretched as far as Ur in Mesopotamia, with Afghanistan serving as a vital connector between the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Indus Valley.

Religious and Social Developments

Evidence of early religious practices has been uncovered at sites like Mundigak and Deh Morasi. These sites contain structures that may have served religious purposes, such as altars and temples, along with ritual objects like goat horns and copper seals. These findings highlight the spiritual and ceremonial importance of animals, particularly goats, in early Afghan societies.

Mother goddess figurines, right, from Mundigak, left,

from Deh Morasi Ghundai, 3rd Millennium EBC.

The Neolithic sites in northern Afghanistan also demonstrate early signs of settled life and ritualistic burial practices, laying the groundwork for the development of later civilisations in the region.